How does a refrigerator work?

It takes heat…

We know from last week that objects at different temperatures tend to move toward equilibrium as we move forward in time. That is to say, in general, if you put a hot thing next to a cold thing, the cold thing warms up and the hot thing cools down. This observation is one consequence of a principle known as the [second law of thermodynamics], or 2LTD for short. It’s a pretty fundamental observation that anyone can observe in daily life – but how can we exploit it to do something useful?

Refrigerators are textbook examples of such an exploitation of 2LTD. So are internal combustion engines, but we’ll discuss those another time. Fridges are a better place to start because they’re surprisingly simple, and so make a great jumping off point for understanding how lots of systems work. Today, then, we’ll walk through the four-part cycle1 that keeps your oat milk from turning nasty.

There are three background facts that help this cycle make intuitive sense.

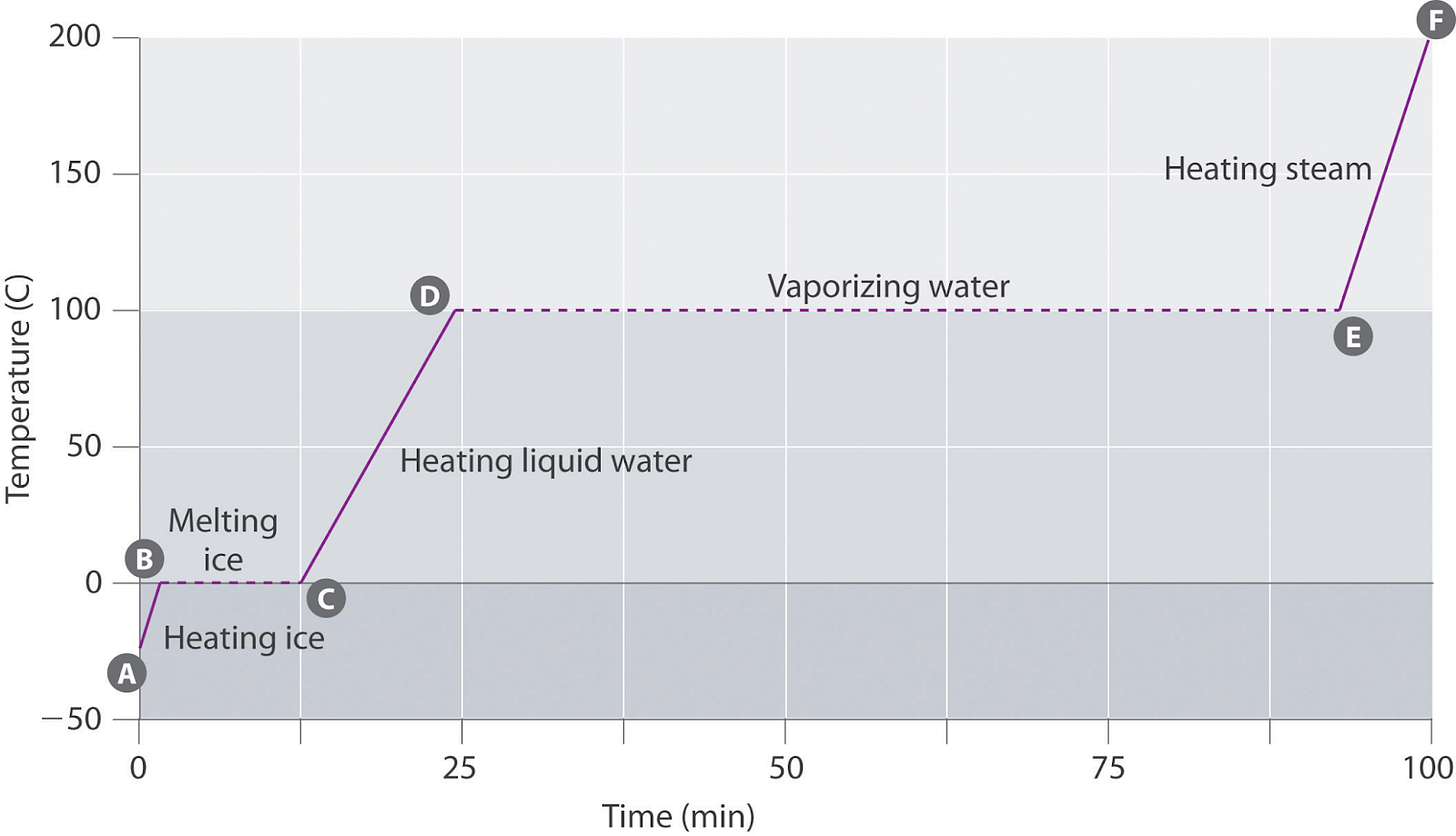

The first background fact (F1) is that when a substance changes from one phase to another (e.g. a liquid boiling into a gas), it remains at a constant temperature until it has undergone the change in its entirety For example, if you heat water continuously on the stove, its temperature will rise until it reaches 100º C and begins to boil. From that point, all the energy the stove is adding to the system goes toward transforming the liquid into a gas. The temperature of the system as a whole remains at 100º C until all of the liquid water has turned to steam, at which point the temperature begins to rise, assuming heat is still being added. One implication of this is particularly relevant to us: for a substance near its boiling point we can add or extract heat from the substance without changing its temperature.2

The second (F2) is how gasses tend to behave in response to changes in temperature, pressure, and volume. Temperature measures how hot or cold something is. Pressure measures how much force is exerted upon a surface. Volume measures how much space something takes up. The “ideal gas law” describes the relationship between these three quantities in gasses. I’m going to paraphrase it3 as V=T/P. There are many ways to think about this. The most useful one for our purposes is to say that when a gas is confined to a given space, you can increase its temperature by applying more pressure to it. See how this satisfies our ideal gas relation: if V is constant, T and P must move together. (Note that while liquids are much more complicated than gasses, this relationship is more-or-less valid for the purposes of understanding the internals of a fridge.4)

The third (F3) is that in general, lower-pressure gasses have a lower boiling point than higher-pressure gasses5. For example, the boiling temperature of water, 100º C, only holds at sea level, under the pressure of a full Earth atmosphere. You can think of the atmosphere’s air as crushing and compacting the water molecules into a liquid state, which they can only “escape” by being granted sufficient thermal energy (heat). As you move above sea level, though, there isn’t as much atmosphere pressing down on the water molecules, and so it doesn’t take as much thermal energy to break the bonds holding them together. That is why the boiling point of water decreases by about 1º C (just under 2º F) for every 1,000 feet of elevation gain. Crucially, the reverse is also true: a high-pressure gas condenses back into a liquid at a higher temperature than a low-pressure gas.

With that out of the way, we can get started making our refrigerator. It essentially has four components:

A thermally insulated box, where the oat milk goes. We will refer to this as the “fridge” from here on out

A fluid called the refrigerant, which flows through the system and undergoes various changes in phase, temperature, and pressure. You can imagine it in an enclosed tube, half of which is inside the fridge, and half outside

A compressor, which forces gas into a narrow opening and thus increases that gas’s pressure

A thermal expansion valve, which limits how much liquid can flow through it, thus reducing that liquid’s pressure.

Since the refrigeration cycle is continuous, it doesn’t matter which step we describe first. I’ve taken the liberty of picking one.

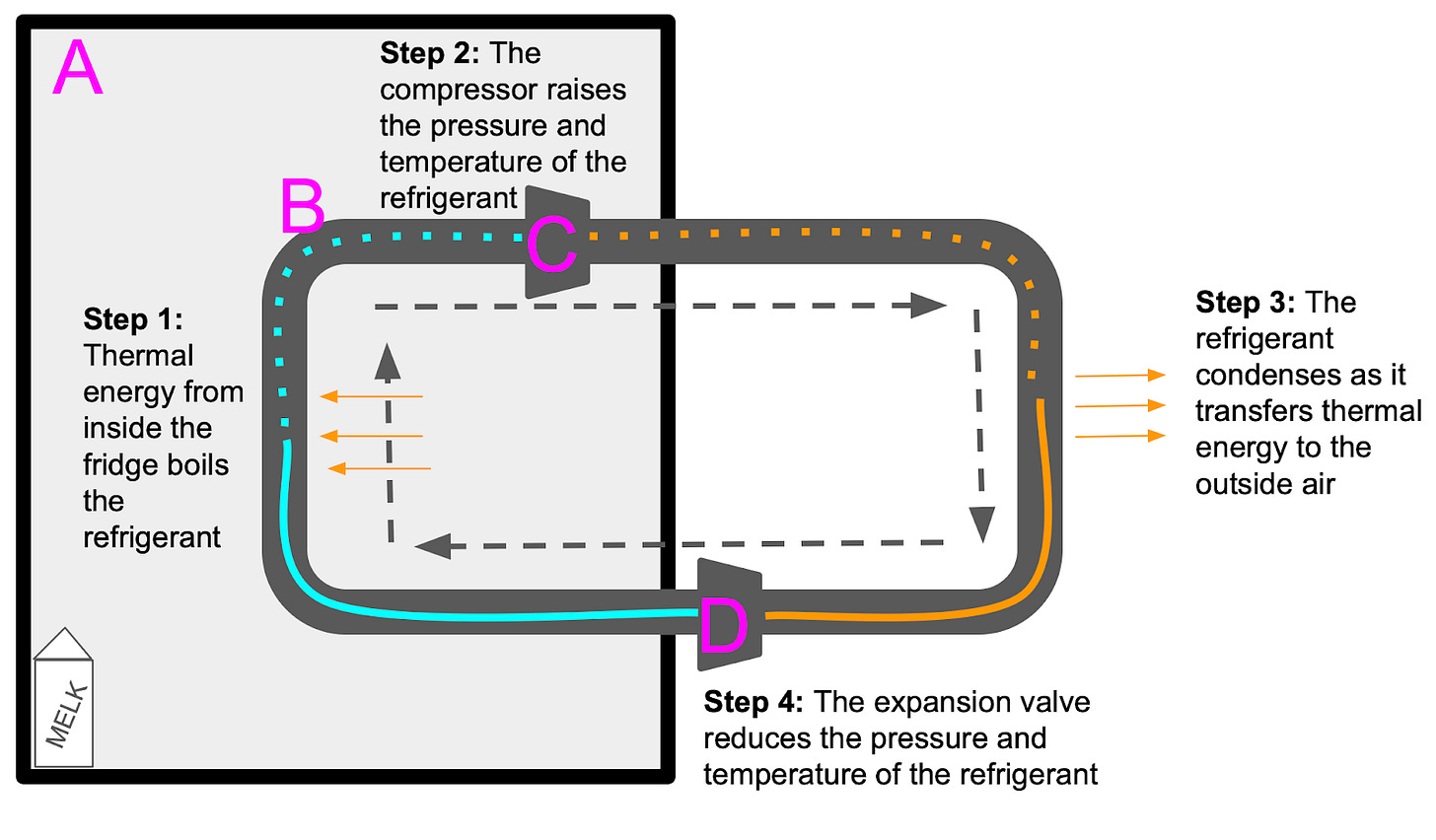

Step 1: Entering the fridge

At the “beginning” of the cycle, the refrigerant flows into the fridge as a cold, low-pressure liquid. Because the air in the fridge is warmer than the refrigerant, there is a thermal exchange “out” from the fridge’s air and “into” the refrigerant (2LTD dictates that the heat will flow in this direction, as it brings the two substances closer to equilibrium).

One important property of the refrigerant is that its boiling point is at a relatively low temperature, so even though the liquid flowing into the fridge is colder than the fridge’s air, the refrigerant “feels” like a pot of boiling water on the verge of turning to steam. As a result, although the temperature of the fridge’s air drops, most of the thermal energy it gives to the refrigerant goes into “boiling” it. As we learned in F1, this heat exchange transforms the refrigerant into a gas without significantly changing its temperature.

Step 2: Compression

Although the refrigerant has just been boiled into a low-pressure gas, from the fridge’s perspective, it is still very cold. The refrigerant now passes through the compressor, which increases its pressure. As we learned in F2, increasing the pressure of a gas in a confined space necessarily raises its temperature. As a result, the refrigerant exits the fridge as a hot, high-pressure gas.

Step 3: Leaving the fridge

The refrigerant is now outside the fridge and comes into thermal contact with the “outside” air (i.e. the air in your kitchen). The refrigerant undergoes a second heat exchange. This time, 2LTD dictates that heat moves “out” from the hot refrigerant and “into” the cooler kitchen air. What is the result of this transfer?

Now that it has gone through the compressor, the refrigerant is highly pressurized. As we learned in F3, this means that the temperature at which it boils has risen. As a result, even though it is much hotter than it was inside the fridge, the refrigerant is once again on the cusp of a phase change, so most of the thermal energy it loses to the kitchen air goes into condensing it back into a liquid instead of changing its temperature.

Step 4: Expansion

At this point, the refrigerant is a hot, high-pressure liquid. In order to complete our cycle, we need to reduce its temperature before letting it back into the fridge. Time to run it through the expansion valve, which decreases its pressure and therefore its temperature (see F2). Now that it is cold and low-pressure, the refrigerant is ready to reenter the fridge and restart the cycle.

So at a high level, the cycle is this:

The inside of the fridge gets colder, and the refrigerant transitions from liquid to gas

Some work is done on the refrigerant, and it heats up

The world outside the fridge gets hotter, and the refrigerant transitions from gas to liquid

Some work is done on the refrigerant, and it cools down

In this image, dotted lines indicate a gas and solid ones a liquid:

Can we state all this even more simply? Always!

How does a refrigerator work? It removes heat from inside a box and pushes it somewhere else!

What’s so cool about 2LTD is that the heat exchange involved in the refrigeration cycle happens “automatically.” The “work” in steps 2 and 4 is simply the energy required to run the compressor and the expansion valve – we don’t have to do anything extra to make heat flow into a higher-entropy state. You can see how this idea of moving heat is quite powerful, and lends itself to other kinds of devices. An air conditioner operates under the exact same mechanisms as a refrigerator, but moving heat from your home into the outside world. A heat pump, meanwhile, does the reverse. It takes heat from the outside world and moves it into your home.

Well, so ends my four-year hiatus from Conversational Physics6. Next week, I may return to the topic of time, or discuss something else entirely!

Note that there are many such cycles, this is just the most common one, and is called vapor-compression refrigeration

This is all somewhat oversimplified. The exact relationship between temperature, pressure, and phase is messy and varies widely between substances

I’m just removing a couple of constants, which are needed for the units on both sides of the equation to match.

It’s not quite correct to use the word “pressure” when speaking about both liquids and gasses at the same time. If you want, you can substitute the phrase “high-pressure liquid” with the phrase “combination of a liquid substance and a high-pressure vapor of that same substance”

Note that this relationship does not hold for water’s freezing temperature, because both water and solids are strange in ways we can discuss another time